Some Dates

While pondering the fate of Grandma Hannah, I wondered about her life that led to confinement. I found it difficult to believe that Hannah would be in what they then called a ‘lunatic asylum’ for over twenty years if all she had was consumption. I studied some of the dates associated with her life and put together this chronology:

23 Sep 1820: Hannah was born

1830: Hannah’s mother Elizabeth Williams died

26 Aug 1845: Married to Charles at age 24

11 Dec 1847: Daughter Ann was born

22 May 1849: Daughter Elizabeth was born

11 Jul 1851: Son Charles was born

9 May 1854: Son Samuel was born

28 Jul 1856: Son John was born

1 Jan 1858: Oldest child (Ann) died at age 11

12 Jan 1858: 4th child (Samuel) died at age 3

28 Jan 1858: Son Robert was born

7 Feb 1861: Hannah’s father William Hubbard died

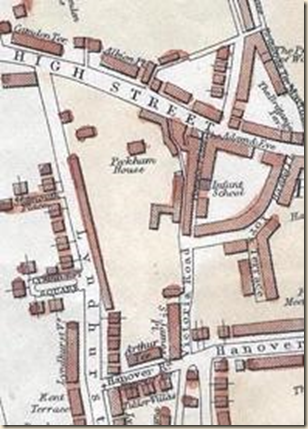

23 Mar 1861: Hannah committed to Peckham Asylum

27 May 1861: 5th child (John) died at age 4

13 Dec 1867: Transferred to Brookwood Asylum

3 Sep 1873: Husband and two sons immigrated to SLC

28 Jun 1883: Hannah died at Brookwood at age 62

The dates alone tell a very sad story. Her mother died when Hannah was a young child, so she must have been raised by her father. Was she close to her father? When Hannah was 37 and nine months pregnant with Robert, two of her children passed away within days of each other. How hard is it to bury your children, even when you’re not pregnant? Three years later her father passed, and it was just six weeks after her father passed that Hannah was committed.

Egham is Dark

England is located quite far north, and the winters are thus dark and gloomy. Egham is 51° north of the equator. From a North American perspective, that is similar to Calgary, Canada. In contrast, Salt Lake City is 40° north, and Chicago is 41°. Antelope California is 38°, and Houston is 29°. So, Salt Lake City is roughly midway between Houston and Calgary, latitudinally. Put in other words, Calgary and Egham are about as far north of Salt Lake City as Houston is South.

For example, on the day I’m writing this, Christmas day 2010, Sunrise was at 08:07 in Egham, and sunset at 15:59, leaving less than eight hours of daylight. (In contrast, the sun rose at 7:50 in Salt Lake City, and set at 17:05, yielding over nine hours of daylight. Stockholm had a little over six hours.) The sun hangs low in the sky in the wintertime here in the UK, and despite the fact that there are fewer clouds than usual today, the sky is gray and the sun is so dim I can look directly at it.

I’ve struggled myself with seasonal depression here in London due to the lack of sunlight. In the winter months, my brain crumbles. Besides horrible lows in mood, thoughts dissolve in my mind like sugar in water. They just disappear while I’m thinking them – I have real trouble hanging onto ideas. My ability to make connections is severely limited and I’m easily confused with things that otherwise click easily for me during the summer months. Brain energy is low making it very difficult to be productive at work. Problems at work that I can normally deal easily with in the summertime become difficult in the winter, and my brain is sluggish; it slogs through tasks in slow motion as if having to wade through waist-high deep water. This is a form of dementia.

I’ve learned that aggressive vitamin D and magnesium supplementation with other nutrients goes a long way towards alleviating the effects of dementia and depression. It also helps significantly to visit the sun through travel, whenever possible. Back in the mid-nineteenth century, however, our ancestors had no knowledge of vitamin D and magnesium, and the Sherwood family certainly did not have the opportunity back then to bop down south to Spain or Egypt for the weekend. Certainly the lack of sunlight and nutrition could have contributed to Hannah’s problems and caused her to snap with the compounding stresses of the deaths of her two children, possible postnatal depression associated with the birth of her son Robert immediately following those deaths, and finally three years later, the passing of her father - her sole parent since the age of 9 or 10.

On the other hand, maybe the lack of sun had nothing at all to do with Hannah’s condition. But in any case, having a small degree of experience myself with the struggles associated with depression and dementia gives me a bit of an insider’s understanding of what Hannah may have been going through.

Why was Grandma Committed?

The Woking library had other documents from Brookwood that I dug into. These documents provide further pieces to the complex puzzle that was Hannah’s life.

One item of interest was the patient admittance register, giving details of Hannah’s state at the time of admittance:

- No. in order of Admission: 315

- Date of Admission: Dec 13 [1867]

- Christian and Surname at length: Anna Sherwood

- Sex: Female

- Age: 46

- Condition as to Marriage: Married

- Condition of Life, and previous Occupation/Religious persuasion: Tailors Wife, Ch. of E [Church of England]

- Previous Place of Abode: Egham

- County, Union, or Parish, to which chargeable: Windsor

- By whose Authority sent: C. W. Furse O. C., E. Simmons R. O.

- Dates of Medical Certificates, and by whom signed: C. V. Ridout, March 23 1861

- Form of Mental Disorder: Dementia

- Supposed Cause of Insanity: (blank)

- Bodily Condition, and Name of Disease, if any: Moderate

- Epileptics: (blank)

- Congenital Idiots: (blank)

- Duration of existing Attacks: 6 years, 9 months

- Number of previous Attacks: (blank)

- Age on First Attack: 36

- Date of Discharge, Removal, or Death: June 28, 1883

- Discharged or Removed: Died

- Observations: D°.

Patient Record

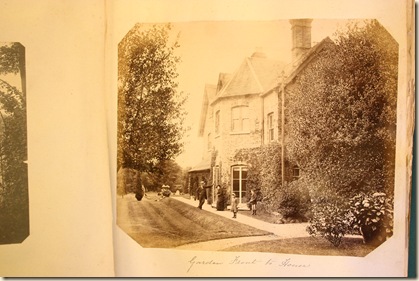

The next document I found gave me a bit of a shock; be gentle when you read it. The doctor was required to examine the patients annually, and a record was kept of the results of the examination. The first entry stated the details of the transfer: that she had been brought in by her brother, Thomas Hubbard of Egham, and that she had been transferred to Brookwood from Pekham House:

The handwriting is difficult to transcribe, and I may have made mistakes, but here’s my best stab at it:

“History. Her malady was marked at the onset by her destruction of p.. .. by heating & burning. has i.., & used 'profane & obscene' language in answer to questions. Set the house on fire & nearly suffocated her children. From Peckham House she is reputed as dangerous to others & to have been employed at ‘scrubbing & needlework, but most destructive…, cutting up & burning.’”

“State in admission: In moderate health. Talks rapidly, .., & for the most part incoherently. Irrational in replies to questions. Says that they tried to ‘derange’ her at Peckham, but cannot explain how. … much in her statements. Has scars of wounds over the trachea which she … were caused by her own act. … sometimes being very animated.”

The record continues with brief reports of her condition every few months until her death. The reports state things like she kept herself clean but refused to participate in her tasks, that her language was offensive and she was abusive to other patients and excitable at times.

It sounds to me like she was a real handful. But surely Grandma was not always like that. The report lists the age of her first attack as 36. That puts the year as 1856/57. Interestingly, this is before her two children died, so she was already suffering by that time, if the report is correct. It’s very possible that the stress of losing her children and finally her father caused her to break to the point that her family could no longer deal with her and she put her children in jeopardy. In any case, she was truly sick and, although the doctors did the best they could with the limited medical understanding they had, they did not have the knowledge of how to help her.

How Did Hannah Die?

The final report gives details of Hannah’s death:

She had diarrhea, temperature of 100 and pulse 120, but did not complain of any pain. She did not take her food very well, “which is confined to beef, tea, milk etc. and brandy. This morning early she was found much worse and in a state of collapse from which she never rallied & died.”

“A post mortem disclosed an abscess situated at the head of the pancreas which did not show any signs of cancer neither did the liver which was fairly healthy & congested, the abscess had burst into the transverse colon which was adherent to it, the rest of the colon (descending) being the seat of chronic inflammation.”

“Cause of death:

1. Abscess of Pancreas

2. Inflammation of the bowels.”

What About Hannah’s Family Through All This?

I found it hard to reconcile that Hannah’s husband and two sons abandoned her altogether when they sailed for America, leaving her behind alone. It still bothers me a little bit to be honest, but at the same time, they had to put their lives back together the best they could without her, under the circumstances. It must have been very difficult for them.

At some point Hannah’s husband moved to London and collected his son Robert back from the orphanage; I like to believe he moved to London because he wanted to be closer to Hannah when she was in Pekham House.

I wanted to find some evidence that Hannah’s family had not forsaken her altogether. Brookwood was not easily accessible from London back then, and there was no evidence that they ever visited her. But I hoped to find some form of correspondence in the years between Hannah’s admission in Dec 1867 to the time her husband and two sons set sail from Liverpool to America in 1873.

The library had trays filled with literally hundreds of letters and other documents, bound by month. The doctor apparently had one filing system – all incoming correspondence was put into a single pile, regardless of the type of correspondence. Everything was kept in the same pile – letters from families, letters from patients themselves to the doctor, employment enquiries, bills – everything. At the end of each month the documents were all bundled together with twine and stored away somewhere.

These bundles are now kept in trays in the library in Woking, and I was permitted to look at them. The archivists helped me to undo the twine, bundle by bundle, and left me alone to carefully unfold each document to see if it had relevance to our family.

It was one of the most tedious tasks I’ve ever done, to go through those trays of dusty 140+ year old letters, one at a time, hour after hour. But look what I finally found, from Hannah’s son Charles:

The letter is dated “Hastings, Feb 14. 70”, and the doctor noted that it was received on the 16th:

Sir

I would feel very much obliged if you would be so kind as to write and let me know how my mother Mrs. Anna Sherwood is in health and mind.

Yours respectfully

C. Sherwood

This is the only letter I found out of all those documents. But the date is interesting. We know that the three of them were baptized in 1869 and left for Liverpool on September 1, 1870, where they lived for three years before sailing to America.

It kind of looks to me like they were trying to decide whether to go to America, leaving Hannah behind. It must have been a hard decision - to leave England represented a pretty much final closing of the door to Hannah. This letter shows that they did not take the decision lightly. Based on the medical records the doctor kept, we can presume that the doctor’s response to Charles was most likely bleak. Had there been some change for the positive, perhaps Hannah’s family would have stayed in England, ready to collect her home at some future point.

Is all this too much information? Maybe. Do we really want to know this tragic information about Grandma? Maybe not. But maybe we do, if there is something to be learned. And especially if there is something about Grandma that has been passed down more or less to each of us, her descendents. It’s also possible that medical science may eventually be able to explain what really happened with Hannah, so we need to preserve these clues for that time. For now, I’ll leave the conclusions, if any, to the individual reader to sort out for him/herself. If anyone would like to delve deeper into Hannah’s medical reports, let me know and I’ll send the rest of my photos.