Wednesday, 1 January 2020

Don't ridicule a child's parent in front of them, even in jest.

A few of my colleagues came throughout the morning to meet the boy, and welcome him to the office. My desk is located right outside the room where my supervisor was working, and I could hear all of the conversations my colleagues had with the boy and his dad.

One conversation I overheard is the subject of this blog. The woman took interest in what the boy was working on, and for some reason decided to use the moment to tease my supervisor in front of the boy. "We don't need your dad, do we!" was one comment, that she repeated a few times. "He's not as smart as we are, is he!" "We've got this down without him, don't we!" Each statement was phrased as a question that was meant to lead the boy to agree.

I have no idea how my supervisor felt as a result of those comments. If it had been me, I would have been angry and hurt. I'm sure he was at a loss as to how to respond.

So was I. I sat at my desk trying to think of something to say to counter the assault. I was angry at the woman, and angry at myself for not knowing how to react. My slow brain failed me and it wasn't until I'd slept on it, angrily replaying the moment over and over, that I finally came up with something that I wish I had said. I hope I will remember it if I'm ever in a similar situation. I wish I had gone into the room and said to the boy, "You know she's just joking, don't you? Your dad is one of the smartest people I know. He is well-respected here. We would be at a loss to do our jobs without his guidance." And all of that would have been true.

When someone brings their kid to work, they are showing the kid off to their *second family*. But they are also showing their kid what they do all day. They are using it as a teaching moment and a bonding moment. Why in the world would someone think it is funny to sabotage that by driving a wedge between the kid and his parent?

Kids don't have well-developed bullshit detectors. Imagine the seeds that were thoughtlessly and inappropriately planted in the boy's trusting mind, about someone he needs to rely on. What kind of message did that boy receive from the woman? That it is ok to ridicule your parent in front of others? That his dad may not be respected by his colleagues? That his dad doesn't really know what he's doing?

I hope I will learn from this scenario. It reminds me how important it is to think through situations like this ahead of time in order to be prepared to respond. Other situations to think through might be:

* What to do if someone makes a racist comment against someone in a crowd

* What to do if someone is threatening another person

* What to do if someone is having a medical emergency and others around are ignoring it

What do you think I could have done in this situation?

Thursday, 1 January 2015

Retirement Investments, Cats and Cows

They call them “relationships”. That’s what the guy at the bank wanted to build when he asked me to come in for a chat last August. Like a stray cat that’s received food and milk from me before, he just wouldn’t go away. I think there must have been a question about school, but whatever it was that got me started, I was soon telling him all about pesticides and GMOs and rain water and the loss of top soil and CAFOs and super weeds and seed monopolies; those who know me know that it’s not hard to get me going on those subjects. “You know, Mary,” and I admit I didn’t see it coming from him – the “M” word - “… your 401(k)s are likely invested in Monsanto.”

Stunned. Not sure, but my jaw may have been on the floor. How could I have been so dense? I would never, ever invest directly in companies like Monsanto or Dow, Chevron or BP, but it had never occurred to me to scrutinize my 401(k)s. There it was, the ugly reality of our financial world – it’s too convenient and too opaque. I felt like a naive pawn entrenched in the ever increasing control of corporate giants running a corrupt system that seems to be spreading stealthily and steadily throughout our culture.

I knew he was probably right, and that day I immediately started searching for alternatives. I’m the type of person who prefers to leave financial matters in the hands of experts and worry about other things instead. I have no head for money, and the fact that I spent ten years of my life in the trading industry is pretty ironic. I used to tell my colleagues at Getco that the day I would start trading would be the day Getco would go down the tubes. But I loved to make computers talk to each other, and my colleagues tolerated my lack of money savvy for the most part. 401(k) management was something my financial advisor used to help me with, until he retired eight years ago. Since then my 401(k)s have just sat there, except that I continued to contribute to them through paycheck deductions. But now, suddenly, I had a reason to get smart about my two 401(k) accounts, a new mission to fill, a horrible problem to solve.

I learned about SLoFIG (Sustainable Local Food Investment Group), which would have been exactly the kind of thing I would have loved to invest in, but I couldn’t afford it. (Thank heaven for people who can, and do!)

I learned about ethical investment funds, but was having trouble identifying any in the US. Ethical funds include companies that try to improve the environment, maintain fair trade standards, and exclude products that are detrimental to health, such as tobacco and pornography.

It wasn’t long before I received another invitation from my “friend” at the bank. He, too, had been working on my problem; of course he had his eye on my 401(k)s and wanted to give me a reason to let him manage my retirement funds. He had identified three funds that he thought I should take a look at: the Neuberger Berman Socially Responsive Equity Strategy, the Calvert/Atlanta Large Cap SRI Strategy, and ClearBridge Investments Large Cap Growth ESG (Environmental, Social, Governance). As I looked the funds over, I realized that they did not completely hit the spot either, although they were certainly better than what I had.

Then my friend gave me the lowdown on his fees, which came to – not hundreds – but THOUSANDS of dollars. Per year. I felt sick and weak. I had to face a very difficult question: how badly did I not want to invest in Monsanto?

The answer was – very badly. Badly enough to sign the papers to transfer one of my two 401(k) accounts to an IRA at the bank; thinking the other might follow once I became more comfortable with the whole situation. I left the bank feeling huge relief that my money would be more responsibly invested, that I could tick that item off my todo list for now.

Life is full of twists and turns, and sometimes remarkable surprises. The very next day at a Land Connection board meeting, we were brainstorming about the need to find ways to make more land available to small farmers who would transition the land to organic, and one of the other board members casually mentioned that 401(k) plans usually hold enough money to purchase a small farm; owners can roll-over the funds into self-directed IRAs, which allow alternative investments (with certain restrictions), including farmland. The investor partners with a farmer who needs land to get started in farming, and the beauty of the idea is that, by the time the investor is ready to retire and start using the funds, the farmer is established and presumably ready to purchase the land from the investor.

I nearly fell out of my chair. Of course! The perfect investment is one which is completely in line with one’s passions, which for me is not funds, equities or bonds at all, and certainly not Monsanto. My passion is sustainable agriculture and healthy food. The thought that I may be able to use my retirement funds to invest in an independent and responsible farmer, who would steward a small parcel of land in the manner that we both believe is healthy, gave me new purpose.

I am loath to go back on things I’ve agreed on, but the next day I called my friend at the bank to ask what the status was of my 401(k) roll-over. “I’m sorry, Mary,” he apologized. “We’re usually much quicker with these things, but the guy who sets these things up had to go out of town. But we’ll get this done for you in the next couple of days.” Whew! “Uh, what would be my chances of cancelling the transaction,” I asked. A cow could have fallen into the deep silence that followed. “Talk to me, Mary,” he finally said. Relationship managers have lousy days, too, and I hated to make his go sour. But I had to.

Self-directed IRAs (SDIRA) are certainly not as straightforward to set up and manage as 401(k)s, which are made easy because of employer involvement. Doing the research to step out on my own has come with a huge learning curve, but has also been an interesting adventure, like planning a long hike in some exotic place. Since I will be investing in something I believe is very important, my research has taken on meaning and an urgency beyond safeguarding my retirement funds.

My next few blogs will include some of the things I have learned about SDIRAs. These are things I don’t want to forget, and perhaps my notes will help somebody else out there who, like me, may be trying to find a better way to invest their retirement savings.

Wednesday, 2 April 2014

Feeding The World

The following is a presentation I gave to my Community Health class. I was the final presenter in my group of six, on the topic of healthy food access. The others talked about:

- What is a food desert

- Healthy food access in Chicago

- How does Chicago compare to other urban areas

- Intervention efforts

- What is healthy food

My part was on “The global challenge”. Although my group did a spectacular job with their respective parts, I am only including my own contribution in this blog.

The Global Challenge

When the topic of feeding the world comes up, the first thing we think of is the problem of the world’s population, now at 7 billion, increasing beyond the earth’s capacity to feed us all. We forget that the context of the food security challenge includes many other factors:

- Urbanization

- Growing Inequities

- Human Migration

- Globalization

- Changing Dietary Preferences

- Climate Change

- Environmental Degradation

- Trend Towards Biofuels

In 2002, the World Bank and United Nations collaborated to carry out a consultation to determine whether an in-depth assessment of international food security was needed. Two years later, they concluded that such an assessment should be undertaken, and they launched a massive, international effort that resulted in a 600-page scientific report, prepared by 400 experts from 52 countries. There were two rounds of peer reviews by 400 reviewers from 45 countries, including governments, organizations, and individuals.

58 countries accepted the final report in 2008, plus an additional three (yellow), which accepted it with reservation:

The objective of this report is clearly stated:

This Assessment is a constructive initiative and important contribution that all governments need to take forward to ensure that agricultural knowledge, science and technology (AKST) fulfills its potential to meet the development and sustainability goals of:

- The reduction of hunger and poverty

- The improvement of rural livelihoods and human health, and

- Facilitating equitable, socially, environmentally and economically sustainable development

A section of the report included a summary of ten concerns, of which I only presented three. All ten were given out as a handout, for reference:

Agriculture At A Crossroads: Global ReportConcern #1The fundamental failure of the economic development policies of recent generations has been reliance on the draw-down of natural capital Concern #2Failure to address the “yield gap” Concern #3Modern public-funded AKST research and development has largely ignored traditional production systems for “wild” resources Concern #4Failure to fully address the needs of poor people (loss of social sustainability)

Concern #5Malnutrition and poor human health are still widespread

Concern #6Intensive farming is frequently promoted and managed unsustainably, resulting in the destruction of environmental assets and posing risks to human health

Concern #7Agricultural governance and AKST institutions have focused on producing individual agricultural commodities (e.g. cereals, forestry, fisheries, livestock), rather than seeking synergies and integrated natural resources management. Concern #8Agriculture has been isolated from non-agricultural production-oriented activities in the rural landscape:

Concern #9Poor linkages among key stakeholders and actors Concern #10Since the mid-20th century, there have been two relatively independent pathways to agricultural development:

o Agricultural R&D o International Trade

o Relevant to local communities (IAASTD, 2009) |

Concern #1

The fundamental failure of the economic development policies of recent generations has been reliance on the draw-down of natural capital.

- 80% of oceanic fisheries are being fished at or beyond their sustainable yield

- The world’s forests lose a net 5.6 million hectares (an area the size of Costa Rica) each year

- Half the world’s population lives in countries that are extracting groundwater from aquifers faster than it is replenished

(Brown L. R, 2012)

Concern #5

Malnutrition and poor human health are still widespread

- Research on the few globally-important foods (cereals) has been at the expense of meeting the needs for micronutrients

- Wealthier consumers are also facing problems of poor diet

- Increasing concerns about food safety

The USDA recommends that fruits and vegetables comprise about 50% of our food plate, yet fruits and vegetables represent only about 35% of global production. Grain production, on the other hand, represents about twice the amount recommended for a healthy diet.

In my pie chart, I split out corn from the rest of grain production, because corn is an interesting product in our food supply. Not only does this single crop dominate the rest of food production, but it is used for many things besides food. For example, about 30% of the corn crop is used for high fructose corn syrup. Another 30% is used for fuel. This is a problem, because the price of food in our market system is inextricably linked to the price of fuel.

What is driving the disparity between the USDA plate and global production? Is it supply, or demand? If demand, who is fueling that demand – could it be the suppliers? Something to think about.

Concern #6

Intensive farming is frequently promoted and managed unsustainably, resulting in the destruction of environmental assets and posing risks to human health

- Land clearance

- Soil erosion

- Pollution of waterways

- Inefficient use of water

- Dependence on fossil fuels (agrochemicals/machinery)

The Water Cycle: The existence and movement of water on, in, and above the Earth, between the atmosphere, land, water bodies, and soil. Earth's water is always in movement and changing states, from liquid to vapor to ice. The water cycle—a physical process—including the movement and changing state of water affects plant and animal (including human) life.

The Mineral Cycle: The movement of minerals or nutrients including carbon, nitrogen and other essential nutrients. This physical cycle affects plant, animal and human life.

Energy flow: The most basic physical processes within an ecosystem are photosynthesis and decomposition. Energy flow describes the movement of energy from the sun through all living or once living things.

Community Dynamics (Succession): Ecosystems, plant and animal communities are ever changing. Community dynamics, a biotic process, describes the never-ending development of biological communities.

Source: Essig, 2013

Nature is full of cycles; it is when those cycles are broken that a process becomes unsustainable. To be sustainable over the long term, farming processes and methods should respect the cycles of nature. These four critical cycles are four panes in the window of our ecosystem; all work together synergistically in a healthy system.

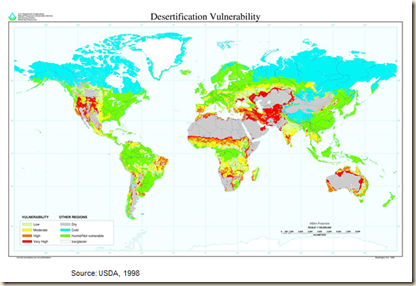

Desertification Vulnerability

- Dust storms carrying 2-3 billion tons of soil leave Africa each year

- Roughly ⅓ of the world’s cropland is now losing topsoil faster than it can be reformed

(Source: Brown L.R., 2012)

Holistic Management

After and Before: Kariegasfontein ranch in Aberdeen, South Africa (Savory Institute, 2014)

Alan Savory is leading an effort using a paradigm he calls “Holistic Management,” resulting in successful healing of deserts: 15 million hectares on five continents. He claims that slight increases in organic matter over huge portions of the earth’s land surface area, would result in putting masses of carbon “back where it belongs – in the soil – and more importantly, where it can actually do some good. Organically rich soils feed soil bacteria, protozoans, and fungi, active populations of which lead to ever greater plant-available nutrients and less dependence on outside fertilizer inputs.” (Savory, 2013)

Healing Tree Farm

Healing Tree Farm, near Traverse City, MI, 26 May 2013

Intensive use of pesticides kills the soil.

The green portion of land in this photo is near the farmhouse; pesticides were not applied there. The brown portion was a field that received heavy pesticide and fertilizer inputs for several years. Not much will grow there now, not even weeds, without significant quantities of inputs. The land is now being transitioned to a permaculture demonstration farm. The land will eventually heal over several years, given healthy management.

I have a favorite quote about the importance of soil from a farmer friend whom I respect and admire very much, Henry Brockman:

Highly nutritious food comes from a healthy soil that is part of a healthy farm that is part of a healthy environment. This circle of health is generated by farming practices that are based on the goal of protecting and enhancing all life, from the lives of the insects, worms, and arthropods of the vegetable field to the lives of the wildlife and domesticated life who inhabit the environment around the field.

The basic tenet of this kind of farming is to protect and enhance the tiny lives of the microorganisms of the soil.

Synthetic fertilizer, which should be a life-promoting substance, actually deals in death. And it deals in death in many ways, polluting air and water as well as killing soil life and disrupting the soil’s intricate system for naturally providing plants with nitrogen. (Brockman, 2001)

Phosphorus

Source: Elser & Rittmann, 2013

The ‘P’ in ‘N-P-K’ fertilizer is for phosphorus, one of the most important nutrients to plant and animal life. Traditionally, ground-up rock phosphate has been applied sparingly to farmland; it is not water soluble so the phosphate becomes available to plants only very slowly, over a period of years. In recent years the industry started treating the phosphate rock with acid to make it water soluble: “super phosphate”. This is used in industrial farms and is immediately available to plants, resulting in significant growth. That’s all well and good, except that excess phosphate, being water soluble, leaches into the ground water and makes its way to streams and rivers, and eventually to the oceans. There is a dead-zone in the Gulf of Mexico where no aquatic life can exist, because of this problem. (Herman Brockman, in Gelder, 2012)

- 20 million metric tons of Phosphate in fertilizers were applied in 2012 worldwide.

- Phosphorus comes primarily from Morocco (75%), #2: China (5.5%), #7: US (2%)

- Phosphorus use tripled between 1960 and 1990 (IAASTD, 2009)

- Extrapolating this trend, the US will become entirely reliant on imports within 3-4 decades. (Elser & Rittmann, 2013)

The series of phosphate cycles shown above illustrate a potential solution to upcoming phosphate shortages. The “current” cycle shows that mined phosphorus is the source of about 90% of the phosphate used to fertilize soil and crops; another 10% comes from weathered phosphorus. The phosphorus mines are limited. Another source of phosphorus that is currently only minimally tapped, is from animal, food, and human waste.

If we were to do a better job of recycling the phosphorus from our waste, we would reduce the need for the water-soluble fertilizer, reduce erosion and runoff into the water, the water would become less polluted, enhancing the survival of fish populations, as shown in the “transition” and “implemented” cycles of the series above.

Water

Source: Brown L. R., 2012

Are Industrial Methods Necessary?

Source: Liebman, 2008

The agriculture industry tells us that, despite the pollution to our water, air, and soil, despite the depletion of resources such as phosphorus, water, and fossil fuels, despite the health risks of pesticides and the super weeds and the antibiotics and the CAFOs, if we did not farm the way we do, we would not be able to feed our 7-billion mouths. Is this claim true?

A long-term (10 year) study was recently undertaken by Iowa State University, funded by a grant from the USDA. They compared the conventional 2-year corn/soybean rotation typically used, with longer, 3- and 4-year rotations that included one year of red clover, and two years of alfalfa, respectively. With each rotation paradigm, they also compared transgenic crops grown using high inputs of pesticides, with non-transgenic crops grown with minimal use of pesticides.

The results are in. They found the following:

- The 3- and 4-year rotation systems exceeded the 2-year conventional systems in yield by 4-20%.

- Weed biomass was low in all systems without significant variation.

- Net returns were highest for 3-year non-transgenic system, and lowest for the two-year non-transgenic system.

Their conclusion:

These results indicate that substantial improvements in the environmental sustainability of Iowa agriculture are achievable now, without sacrificing food production levels or farmer livelihoods. (Liebman, 2012)

The Global Report also had this to say:

Small farms are often among the most productive in terms of output per unit of land and energy.

And:

Restoration techniques are available, but their use is inadequately supported by policy. (IAASTD, 2009)

It is possible to feed our population, but we have our work cut out for us to help establish the policies that can facilitate equitable, socially, environmentally, and economically sustainable development.

Regulatory change will not happen overnight. Until it does, we can each do our part to influence the transition to sustainable farming methods, by voting with our fork.

I have made a personal commitment to consume food that has been organically grown, using sustainable methods that enhance the health of our soil and ecosystem. I know that this is not possible for many, and it did not happen over night for me; I have been working on this for several years now, taking small steps at a time.

When we talk about food deserts, we are referring to areas where healthy food is not available. We usually think of healthy food in terms of fresh fruits and vegetables. But, if we were to extend our definition of healthy food to food that has been grown to support the health of the environment, we would discover that most of us actually live in a food desert.

Because of my personal commitment, I have searched for organically grown food near campus. I have inquired at every restaurant on Taylor Street between the East and West campuses. The closest restaurant I have been able to find is across the street from the Sears Tower, two miles away. Organic food is also available at the Whole Foods on Canal and Roosevelt Rd. These locations are hardly close enough for me to walk to between classes to buy a lunch, so I pack my own lunch and carry it around with me to all my classes in my backpack. We are in a food desert here on campus.

At home, the nearest Whole Foods is over three miles from my home. The nearest farmer’s market that provides organically grown local produce is about 30 miles away from my home. I live in a food desert. Therefore, I am working on transitioning my backyard to a garden so that I can grow my own produce.

If more people would insist on consuming produce that has been raised sustainably, more farmers would make the effort to respond to the demand. We do not have to wait for our government to do the right thing; each of us can do what we can in our own way, to support the movement towards healing our earth.

References

Aneki.com. (n.d.). Map of the World. Retrieved March 31, 2014, from Aneki.com Rankings + Records: http://www.aneki.com/map.php

Brancaccio, D. (2012, April 30). Soybean prices on the rise, could impact other food sources. Retrieved from Marketplace Morning Report: http://www.marketplace.org/topics/economy/soybean-prices-rise-could-impact-other-food-sources

Brockman, H. (2001). Organic Matters. Congerville: TerraBooks.

Brown, L. (2012). Full Planet, Empty Plates: The New Geopolitics of Food Scarcity. New York: W.W. Norton & Company.

Brown, L. R. (2012). Presentations for Full Planet, Empty Plates: The New Geopolitics of Food Scarcity. Retrieved March 29, 2014, from Earth Policy Institute: http://www.earth-policy.org/books/fpep/fpep_presentation

CME Group. (2014, March 1). Agricultural Commodities Products. Retrieved March 29, 2014, from CME Group: http://www.cmegroup.com/trading/agricultural/

Earth Policy Institute. (2014, February 25). Food and Agriculture. Retrieved March 31, 2014, from Earth Policy Institute: http://www.earth-policy.org/data_center/C24

Elser, J. J., & Rittmann, B. E. (2013, December 25). The Dirty Way to Feed 9 Billion People. Future Tense. Retrieved March 31, 2014, from http://www.slate.com/articles/technology/future_tense/2013/12/phosphorus_shortage_how_to_safeguard_the_agricultural_system_s_future.2.html

Essig, M. (2013). Nurturing Our Planet: The Health Of The Ecosystem Processes. Savory Institute.

Gelder, M. (2012, November 16). Interview with Herman Brockman about GMOs. Retrieved March 30, 2014, from Mary's Heights Blogspot: http://marysheights.blogspot.com/2012/11/interview-with-herman-brockman-about.html

IAASTD. (2009). Agriculture at a Crossroads: Global Report. International Assessment of Agricultural Knowledge, Science and Technology for Development. Retrieved March 29, 2014, from http://www.unep.org/dewa/assessments/ecosystems/iaastd/tabid/105853/default.aspx

Liebman, M. (2008). Mixed Annual-Perennial Systems: Diversity on Iowa's Land. Iowa: Leopold Center, Iowa State University. Retrieved March 31, 2014, from http://www.leopold.iastate.edu/sites/default/files/events/Matt_Liebman_presentation.pdf

Liebman, M. (2012). Impacts of Conventional and Diversified Rotation Systems on Crop Yields, Profitability, Soil Functions, and Environmental Quality. Leopold Center for Sustainable Agriculture. Iowa State University. Retrieved March 31, 2014, from https://www.leopold.iastate.edu/sites/default/files/grants/E2010-02_0.pdf

Savory Institute. (2014). Desertification Solution: Holistic Management. Retrieved March 30, 2014, from Savory Institute: http://www.savoryinstitute.com/science/the-desertification-crisis/desertification-solution-holistic-management/

Savory, A. (2013). The Foundation of Holistic Management: New Principles & Steps For Handling Complex Decisions, E-Book One. Savory Institute. Retrieved from http://savory-institute.myshopify.com/products/holistic-management-principles-new-principles-steps-for-handling-complex-decisions

USDA. (1998). Natural Resources Conservation Service Soils. Retrieved March 29, 2014, from United States Department of Agriculture: http://www.nrcs.usda.gov/wps/portal/nrcs/detail/soils/use/worldsoils/?cid=nrcs142p2_054003

USDA. (1999). Feed Yearbook. (D. Decker, Ed.) U.S. Department of Agriculture, Market and Trade Economics Division, Economic Research Service.

Sunday, 23 February 2014

Reflections on Racial Disparity

The following is a paper I wrote February 11 for my community health class; the assignment was to reflect on specific readings about racial disparity.

The readings for this week included:

- Hebert, P., Sisk, J., Howell, E., When Does a Difference Become a Disparity? Conceptualizing Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health. Health Affairs; Mar/Apr 2008, Vol. 27 Issue 2, p374-382.

- Smedley, B., Stith, A, Nelson, A. (Ed.) Unequal treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care (2002). Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press Committee on Understanding and Eliminating Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care.

I gripped the useless steering wheel in front of me, all senses alert, taking in the crackling roar of the windshield grinding relentlessly on the pavement. I was hanging upside down by my seatbelt and realized that I was likely facing my end. A heavy sadness wrapped around my heart with the thought that I would never see Mother again. The roar continued and I waited helplessly in the darkness for the inevitable impact that I hoped would not be too painful.

And then there was a wicked silence that told me the car had finally stopped. Instantly the adrenalin of fear kicked in and I knew it was urgent to get out of the car. On TV, the next thing to happen after a car flips is an explosion. Unlike Starksy on TV, though, who usually did everything right, I released my seatbelt to escape and landed clumsily on my head in a pile of shattered glass. The door was blocked by the weight of the car and the only way out was through the side window. The only thought that drove me forward was “GET OUT NOW!” Never mind that the shattered window still had shards of glass around the frame.

An instant later I was standing several feet away from my car. With huge relief I saw that the car was not in the middle of the Interstate as I’d feared, but well off the road in a field. I looked at my poor car resting strangely upside down, the headlights shining their beacons into the darkness like a lighthouse, the incongruously cheerful strains of Claude Bolling’s Picnic Suite haunting the night from the tape deck still playing away. “I should have turned off the car,” I thought, while the unmistakable fumes of fuel warned me to stay well clear.

Now what? I was a young woman alone in the middle of a cornfield with no homes anywhere in sight. Anyone could easily take advantage of my vulnerable situation as I realized I still faced danger. But so far I was still alive. I did a quick survey: head hurt, neck in pain, back screaming pain, dark blood trickling slowly down both forearms in tiny rivulets like condensing ice water on a glass; my hasty exit through the window had left its mark. Someone was approaching. Friend or foe, I had no choice but to wait.

“Is there anyone in the car?” He was bending over, trying to peer into my dark car. “I’m alone,” I replied. “You ok?” He asked. “Uh, I think so.” “Come with me,” and he extended his hand toward me.

The hand was black.

It was only a flickering moment but it was framed in the context of generations of mistrust and abuse between “us” and “them”. My first encounter with people of Color was as a child in a restaurant in the city with Grandma and Grandpa. All of the people working in the kitchen, collecting the glass dishes from the dining room onto metal carts for washing, were dark. I’d never seen anyone like them before in my all-white community. “You don’t want to be like THOSE People,” Grandma had said. Later as I grew up, I noted that the people with smart jobs were all white. The people cleaning the hotels, picking up the garbage, and washing the dishes, were Black. I had to agree with Grandma, I wanted something better.

In my household, our church was the center of our lives. As a young child, I learned that God had restored his church and reestablished the authority to act in his name using the keys of the Priesthood. Young men were ordained with levels of the Priesthood, starting at age 12, with one caveat: the Priesthood was available only to men who were not of the lineage of Cain. My parents and church leaders tried to explain the unanswerable question: “Why?” For some reason God felt that Blacks were not worthy enough for the Priesthood. Although the church reversed its position when I was a young adult, the damage had already been done in my impressionable youth. I trusted God, and trusted the church like my parents. Even after the church started extending the Priesthood to Black members, shadows of condescension persisted. Eventually I rejected the church and formally withdrew my membership, but was still left with that stain of my upbringing.

That hand was black.

Soon after I moved to Chicago, the springs in my mattress started breaking through on both sides: top and bottom. That mattress, salvaged many years before from somebody’s garbage heap at the side of the road, had been a blessing to me at a time when I could barely afford food and rent, let alone furniture. It was time to find a new mattress, and I didn’t want just any mattress, I wanted one that was 90 inches long to fit my Gelder-sized body. The yellow pages and several phone calls I’d made had yielded only one place in all of Chicagoland that offered the possibility of obtaining a custom-made 90” mattress. They gave me the address of their store over the phone and told me to ring the doorbell at the side door when I arrived.

Ring the doorbell?

I found the address on my map and it took over an hour to drive there from my apartment. As I approached the store I noticed uneasily that the neighborhood was one of “those” that I probably should not be driving around in. I found the store and parked my car across the street and sat in my seat looking at it. Bars covered the windows. The front door was secured with a chain. Graffiti marred the side wall. I checked all of my car doors to make sure they were all safely locked and felt that I should leave. But to leave meant that I would not get my 90” mattress, and I gathered myself up, got out of the car, squared my shoulders, and walked, hardly breathing, across the street and down the alley to the side door. “Who’s there?” someone hollered when I rang the bell. “Mary Gelder,” I squeaked. “I have an appointment.” They let me in and told me someone would be with me shortly, leaving me alone in a small showroom displaying three beds. The walls were covered with posters; a picture of Jesus was in the far corner. Their Jesus was apparently different than the Jesus I grew up with. I could hear some sort of work activity in a room beyond, where I imagined they might soon be making my new 90” mattress. I wondered if I’d made a mistake. I had once managed the furniture department at Sears, and learned the value of a quality mattress. I wondered where on the scale of quality a mattress made by this shop would fall: good, better, or best? Or maybe – worst?

Nobody was coming, so I walked around the room, killing the time by looking at the posters they had on the walls. Each poster featured a Black person accompanied by a brief account of his or her contribution to the Black community. Martin Luther King was among them, but he was the only one I recognized. “Why is it that I’ve never even heard of these apparently great people,” I wondered to myself. The individuals who were prominent enough in Black culture to be so revered by the store proprietor had never even crossed the threshold of my awareness. Was it that I had not paid attention in school, or was my education sorely biased?

That black hand was still extended toward me. He was waiting.

“You should read this,” the nurse told me. I was working at a nursing home in my neighborhood, and had just helped one of the patients to bed, securing her diaper and removing her dentures. I took the newspaper clipping from the nurse and glanced at it. “First Black Woman Graduates” read the headline; a photo showed a young Black woman standing in front of the wrought-iron fence bordering the campus. It was a well-yellowed article about the woman before me, now in her nineties. This woman had refused to be deprived of a college education, had made up her mind despite her race and gender to graduate, had faced the university board and somehow convinced them to admit her. She put up with whatever frictions and prejudices of the student body and faculty that had surely confronted her, and finally graduated, the first Black woman ever to do so from that university. I looked at her lying in the bed before me, a woman ultimately discarded by society into the nursing home where I worked, her eyes now vacant and confused. I wondered if she had made a difference in the world, and whether her insistence on having a college education had paid off for her. I wondered how many doors had later been opened to other women, Black and White, because of her persistence and determination to crack through that racial barrier. I felt something shift in my own opinion towards the Black struggle, and realized that this woman’s courage and persistence was, that night, making a difference to me.

Why was it so hard for me to take that Black hand, to accept his humble offer of help at my moment of critical vulnerability? And why was I so disturbed when I read the suggestion by Hebert, Sisk, and Howell for a thought experiment to consider how a subject’s health “would be different if he were to relive his life to date as a different race?” How would my own health be different had I been born Black? The question shocked me enough to worry about it through the night, unable to sleep. What is it about being Black that bothered me so much at the suggestion?

It is not a question of looks or ability, nor is it an implication that I might be less of a person. It is not even a question of rightness or wrongness, although earlier in my life I did have to confront that senseless perception of race. Rather, the jolt of thinking of myself as Black brings with it a sense of deep loss of opportunity. I have to acknowledge that my life has been easier because I’ve lived in a safe, White neighborhood. Unlike the Black nursing home patient I met, some of the doors I’ve faced have been already open, ready for me to walk through. Being on the “Yes” end of things has made it easier for me to be healthy. “Yes, you can take this class.” “Yes, you can rent this apartment.” “Yes, you can have this job.” “Yes, you can be my friend.” Some of the barriers that would confront me as a Black person are deeply rooted injustices engrained in traditions, religions, role models, music and arts, political systems, and social media. Any success that I’ve enjoyed may be somewhat attributable to the fact that I’m not Black. As pointed out by Hebert/Sisk/Howell, “a person may make different choices if living a counterfactual race in a different social context.” The decisions I’ve made throughout life have stemmed from my response to a fundamental perception of my own social place. I am not relegated to the back seat, and nor were my parents, or my grandparents. In my formative years, I recognized that I belong to a race shared by our nation’s presidents, astronauts, and movie stars. As a White person, I’ve felt that I can, if only I will. Had I been Black, my perceptions, and subsequently my decisions, may have taken different paths altogether. And as a Black person, my interactions with peers, employers, and others in authority over me may have been completely different. The color of my world would likely have been in sharp contrast to what I’ve actually experienced. And that bothers me.

Accounting for the factors of disparity may be much more difficult than the Hebert/Sisk/Howell challenge implies. How can the limitations in education on the one side possibly be quantified along with the bias in education on the other? They cannot. Hebert, Sisk, and Howell demonstrated clearly the difficulties of quantifying disparities by showing that the same data may be used to show bias as well as anti-bias, depending on the artistic use of controls. There is a challenge, then, in identifying that sweet spot in the analysis, a spot that truly reveals the underlying disparity. We know that disparity lies somewhere between two extremes, but pinpointing the extent of the disparity is clearly subject to debate. If we can’t understand the extent of the disparity through analysis, can we hope to heal our racial divide? How can a healthy and fair balance between our races be secured after so many generations of abuse?

Smedley, et al provided an important list of recommendations for mechanisms and controls designed to reduce bias and stereotyping, increase consistency, and improve communication and awareness. Every step represents one means to an important, all-pervading end: trust. Establishing trust on the part of the health provider, and likewise on the part of the individual must be at the heart of any effort to eliminate disparities. If a balance may truly be found, if there is any hope of healing our culture of racism, of tearing down the iron walls around our universities and our hospitals, we must surely develop trust. Considering the historical grip of prejudice pervading our culture, this is easier said than done. But such a balance may have been found, for a moment, for two of us, that night as we stood near my car.

I wasn’t sure I could trust the individual extending his hand, but I hoped that I could. “I’m bleeding,” I said, and showed him that my hands were sticky from the blood dripping from my arms. I didn’t have AIDS or any other dread disease, but I knew he wouldn’t know that and was probably wondering. He likely felt as vulnerable as I did, and I had to give him an opportunity to protect himself if he wanted to. From me.

“Come,” he said simply. He took my bloody hand gently into his, and guided my slow, painful steps carefully across the Interstate to safety. It was a gesture of trust, of acceptance, an acknowledgement of shared risk. As his hand connected with mine, once again I felt something shift in my attitude toward the Black struggle and I found myself ready to accept his healing gift, his touch of humanity.

Friday, 21 June 2013

Response to IL Senate Bill 1666

This is the email I wrote to the Illinois Agriculture and Conservation Subcommittee on Food Labeling yesterday, following the public hearing. I wrote it because the opposition emphasized that the genes inserted into transgenic plants are genes that we commonly consume otherwise, thus implying that there is no harm in eating them in GMO crops. I have sent the email already, but would still really appreciate feedback. I will likely be writing more emails of this nature and hope to get better at it with your help.

Chairman Koehler,

Thank you for sponsoring SB1666 on the labeling of GMO foods. I attended the hearing this morning in Normal out of a strong personal concern for the future of our food supply.

I have a background in technology, having received a Master of Science degree from DePaul in Telecommunications, and a Bachelor of Science degree from UIC in Computer Engineering. I have been a software developer for the past 18 years. A few years ago I experienced some health issues, and launched myself into what I call the "Mother Nature" diet. I emptied my cupboards of processed foods and extracts, preferring to use food in its most natural, whole form. Over time, my body responded to the dietary changes, and with the positive improvements in my health, my interest in nutrition increased. This interest led me to research organic farming methods, and the impact industrial farming has on our ecosystem. Learning about the sources of our food supply led to a deep concern, to the point that I resolved to become involved at a level beyond my own personal interests. I left the world of software behind to return to school, and am now a full time student once again at UIC, working on a Master of Public Health degree in Environmental and Occupational Sciences.

The GMO issue has been especially interesting to me, because of my technical background. In fact, there's a side of me that really hopes that the biotech engineers will one day find success. Although the food industry would like us to believe otherwise, however, success is not yet assured. While the results of independent studies are not conclusive, they do raise sufficient concern over the potential health risks of GMO foods to warrant further study. Unfortunately, long-term impartial studies are not available, leaving consumers, like me, to rely on their own research to make their own judgments for their own health.

I would like to share a few things that I've learned about GMOs that were not addressed in the hearing this morning:

1. The transgene itself is, for me, not the issue of concern; it is rather the process of insertion that poses the greatest risk. While the industry would like us to believe that the insertion of a gene into a new species is a precise operation, it is not. The process most commonly used is called "Transfection by Agrobacterium tumefaciens", and leverages the ability of the bacterium to inject DNA into a cell. The gene is incorporated into the cell's genome at a semi-random location. The resulting location and its ultimate impact on the GM plant are not fully known, even by the technologists supervising the process. Success is declared when the plant expresses the desired trait, but unpredictable side-effects can also result from mutations caused by the insertion, that produce a variety of potentially harmful proteins.

2. The GE technology was initially developed when scientists assumed a one-to-one correspondence between genes and proteins, but we have since learned this is not the case. The DNA "protocol" is very intricate and complex, making the random insertion of a transgene very risky. If the process were equated to software, it would be akin to dropping a small sequence of code randomly into an existing software application. Theoretically, the new portion of code might indeed be useful, but depending on its placement in the application, it could also create havoc, resulting in bugs that might not be realized until much later.

3. Once the insertion is completed, the plant cells are treated with antibiotics to kill off the Agrobacteria before being propagated to crops. Not all are successfully removed, however; some remain on the GM plant to be passed on to future generations; these Agrobacteria can potentially extend the gene insertion to animal cells, or to fungi and yeast, vital parts of the soil ecosystem.

4. The gene is not inserted alone into the plant genome; a stretch of DNA called the "Cauliflower Mosaic Virus" (CaMV 35S) promoter is inserted along with it. This powerful promoter is used to "turn on" the new gene, allowing it to be expressed. This promoter, however, also has the ability and potential to turn on other genes besides the new transgene. It can activate host genes elsewhere in the genome, even on other chromosomes, driving expression of genes in the wrong cells at the wrong time. The insertion of this promoter is of major concern to many scientists.

We are walking a very dangerous line here. Despite the lack of hard evidence against GMOs, many are responding to anecdotal evidence and common sense to steer clear of genetically modified food to protect their own health, as well they should. The lack of transparency by the industry and resistance to disclosure of GMO products adds to the perception of stealth that surrounds the controversy. I do not buy the claims that labeling would increase costs significantly. If GMOs truly add value as they claim, the food industry should be proud to boast about them on their labels.

Thank you for giving me the opportunity to share my perspective. I urge the committee to support SB1666. Labeling of GMO products will help us as consumers to vote for or against this technology, with our food purchases. Labeling will help restore the power of choice to those of us who care about our health and our future.

Respectfully,

Mary Gelder

Westmont, IL 60559

Thursday, 28 March 2013

How The Heck Do Transgenes Get Into GMOs?

Two weeks ago I gave a (group) presentation in my biology class on a 1999 paper by Arpad Pusztai on GMOs (Genetically Modified Organisms). Pusztai was leading a group of scientists at the Rowett Institute in Scotland which was developing a test paradigm that would assure the validity and safety of GMO crops, but to their surprise, they discovered serious health effects that could only have been caused by the insertion of the transgene (not the transgene itself, but the process of insertion). Pusztai was appalled to learn that GMO products were already on the market, and when he publicized his findings, the public outrage was so great that major food chains resorted to removing GMO ingredients from their products in Europe, and legislation was introduced throughout Europe for the labeling of GMO products. Of course the biotech industry fought back, discrediting Pusztai, and he was suspended from the Rowett Institute (which does a lot of research funded by the biotech industry). Later, his paper about the research was formally published (under threat) in ‘The Lancet’, which had the paper reviewed by six peers instead of the usual two because of the intensity of the controversy. Five of the reviewers approved publication; one dissented. During this time, although hundreds of articles were published in Europe about the controversy, only two articles were published here in the States. For some reason the media weren’t as interested here.

For my presentation I wanted to learn about the process of genetically modifying plants, so I dug in. I had heard about the gene-gun, which blasts genes into the nucleus like a B-B gun, where they usually obliterate the cell altogether. In a few cases (1 in 10,000) the cell survives and the new gene lands in the DNA at some random location. Although they used to use that method more in the past (and still do in some cases), it turns out that in about 90% of the cases now, they use a bacterium (Agrobacterium tumefaciens) to do the dirty work, instead. This is a pathogenic soil bacterium that causes tumors in many species of plants. The tumor-inducing genes in the bacterium are deleted, and the desired gene sequence is cloned in the T-DNA of the bacterium. (That, by the way, is the "precise" part of the process that biotech scientists point to in their defense of GMOs. They don’t bother to share the rest of the story.) The plant seedlings are heated to place them under stress, making them susceptible to the bacteria. The bacteria attach to the cell, and using virulent genes in a biological process known as T4SS (Type IV secretion system), they poke the new gene into the plant cell along with a promoter to turn on transcription. This promoter, known as the Cauliflower Mosaic Virus (CaMV), is one of the most powerful promoters known. Depending on where it lands in the plant’s DNA, it can promote not only the transcription of the new transgene, but other genes downstream or even on other chromosomes. This carries huge unintended risks and is the detail in the GMO process that has scientists very concerned. Although Pusztai’s tests did not identify this as THE element that resulted in the deleterious health effects in the rats he was testing, he suspects that it is likely involved.

As if this weren’t enough, once the transgene is in the plant, the A. tumefaciens bacteria are no longer needed, so the plant cells are treated with antibiotics to kill off the agrobacteria before being propagated to crops. It is about 50% effective; some bacteria survive and are propagated to the crops along with the new cells. Unfortunately, this is yet another routine use of antibiotics, contributing to the serious problem we have of increasing bacterial resistance to antibiotics.

The bottom line is that there are huge risks with GMOs. Their safety has not been established, and the few independent tests we do have indicate potential for serious health problems. As these problems are not acute (i.e. immediate and severe), but rather chronic (developed over time), it is very difficult to make the association. Researchers are reluctant to take on the biotech giants, so the tests we so desperately need to understand this technology don’t happen.

Here is a 2009 quote from Pusztai, ten years after his controversial paper was published: "One gene expressing one protein is the basis of genetic engineering, but the Human Genome Project discovered [only] 23,000 genes, and there are 200,000 proteins in every cell. With this discovery, genetic engineering should have disappeared into the dustbin."

I feel like I’m only scratching the surface in understanding the depth of this problem, but I thought I would share what I learned in preparing for my presentation. This is nasty business.

My sources:

• Viral DNA dangers. (2009, June). Retrieved March 10, 2013, from GM-free Scotland: http://gmfreescotland.blogspot.com/2011/02/viral-dna-dangers.html

• Agrobacterium. (2010, December). Retrieved March 10, 2013, from GM-free Scotland: http://gmfreescotland.blogspot.com/2011/04/agrobacterium.html

• Agrobacterium tumefaciens. (2013, March 10). Retrieved from Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Agrobacterium_tumefaciens

• Gene gun. (2013, March 10). Retrieved from Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gene_gun

• Boyle, R. (2011, January 24). How To Genetically Modify a Seed, Step By Step. Popular Science. Retrieved March 10, 2013, from http://www.popsci.com/science/article/2011-01/life-cycle-genetically-modified-seed

• Ewen, S. W., & Pusztai, A. (1999, October 16). Effect of diets containing genetically modified potatoes expressing Galanthus nivalis lectin on rat small intestine. The Lancet, 354, 1353-1354. Retrieved March 10, 2013, from http://www.sciencedirect.com.proxy.cc.uic.edu/science/article/pii/S0140673698058607

• Pitzschke, A., & Hirt, H. (2010, February 11). New insights into an old story: Agrobacterium-induced tumour formation in plants by plant transformation. The Embo Journal, 29, 1021-1032. doi:10.1038/emboj.2010.8

• Pusztai, A. F. (1998). SOAEFD flexible Fund Project RO 818. Report of Project Coordinator on data produced at the Rowett Research Institute (RRI), Rowett Research Institute. Retrieved March 14, 2013, from http://www.rowett.ac.uk/gmo/ajp.htm

• Roseboro, K. (2009, June). Arpad Pusztai and the Risks of Genetic Engineering. Organic Consumers Association. Retrieved March 13, 2013, from http://www.organicconsumers.org/articles/article_18101.cfm

• Smith, J. M. (2003). Seeds of Deception. Yes! Books.

Tuesday, 20 November 2012

Migrant Farm Workers in Florida and Their Struggle for Environmental Justice

October 29, 2012

Introduction

The average American gives little thought to tomatoes. The weekly trip to the grocery store never disappoints; the red orbs are always there, no matter the season. January? No problem. The tomatoes displayed on the shelves in deep winter actually look no different than the ones that graced the same shelves in July. Likewise, when buying a Whopper from Burger King, one simply expects there to be a slice or two of fresh tomato on the patty. Never mind that snow had to be brushed off the car earlier that day; tomatoes are always available. Magically.

Where do those winter tomatoes come from, and what has happened to our system of agriculture that makes it seem so easy to have tomatoes on our dinner plate year round? Most people recognize that the miracle of the tomatoes happens far away in the South, where the sun shines high in the sky throughout the winter months. Beyond that though, there is a void of understanding. There is a hidden and tragic aspect to the seemingly bountiful flow of our most ubiquitous fruit that most people are unaware of. Our system of retailing the abundance of agriculture has detached the consumer from the farm so much that the true cost of our food is not only deeply hidden from the consumer, but that cost is in fact difficult to discover even when a conscientious consumer wants to make the effort to find out.

Some of the worst abuses of farm workers prevail today because the workers are invisible to society.

In this paper I will introduce a group of people who labor in the fields to produce our food, and specifically winter tomatoes. The paper will describe the struggle of migrant farm workers in southwestern Florida to work safely and fairly. I will use indicators described by David Pellow in his book, “Garbage Wars” (1), to show that the working conditions for that group of laborers warrants the label of environmental injustice. The paper will explore some of the injustices that have exploited this class of workers to the benefit of industrial farms and indirectly, to our own benefit as consumers. It will discuss some of the historical background of the injustices in order to help us better understand the roots of the problem. It will identify the multiple stakeholder relationships, and will delve into the specific struggles and actions these workers and others have taken to resist the injustices. Finally, the paper will consider the issues that continue to face the workers in the road towards environmental justice.

A History of Agriculture in Immokalee

The hub of tomato agriculture in Florida is centered in a community in the far southwest portion of the state, called Immokalee. About twenty miles north, the Caloosahatchee River connects the Gulf of Mexico with Lake Okeechobee. Immokalee itself is on high ground, an important feature that attracted agribusiness to the area, because the land doesn’t require draining. Prior to the use of land by agriculture, though, Immokalee was a small cattle town. In 1921, the Atlantic Coast Line Railway was extended south, connecting Immokalee to the rest of the country, facilitating commerce. Construction of the railroad attracted US-born Blacks to the area to fill the need for labor.

In the 1930’s, lumber developed as a new use of the land around Immokalee. Timber attracted more workers, and the sawmill owners built living quarters for the workers. Resin from the tree stumps was sold for use in explosives and medicine, and the stumps were removed for that purpose. Before long, however, the virgin cypress and pine were logged out, and the sawmills had to close down. With the trees and even the stumps cleared out, the land was ready for vegetable farming.

In 1940, Immokalee Growers, Inc. was established as the first packinghouse in Immokalee, and with that, agribusiness began shooting down roots in the region.

With the advent of the Second World War, so many farmworkers left the fields of Florida (and across the country) either to fight in the war or to work in various war industries, that their vacancies left a serious shortage of workers to harvest the crops needed to feed the nation. To answer that need, US president Franklin D. Roosevelt negotiated an agreement with Mexico in 1942 that offered a guarantee of basic protections to Mexican workers. Known as the “Bracero Program”, the Mexican Farm Labor Program sponsored millions of guest workers from Mexico from 1942 to 1964. (2) (3) Many of those workers came to Immokalee.

As land was devoted to agriculture, the need for workers grew, and Mexicans immigrated in droves under the Bracero Program to fill that need. They left poverty and corruption in their home country in the hopes of finding work in Immokalee. Most had very little education and spoke no English, but they had what was needed for the fields: experience and drive. They just wanted to work and make better lives for themselves.

In 1959, American-owned businesses in Cuba were taken over by Castro. During the ensuing revolution, many people left Cuba and came to the Immokalee area because of the availability of work. In 1962, a US trade embargo was established against the purchase of products from Cuba, and this is when big vegetable growers started arriving in Immokalee and agribusiness started to take off in Southern Florida. Improvements in technology (e.g. culture beds, drip irrigation, fertilization, plastic mulching) made it possible to grow tomatoes there, despite the infertile, sandy soil. During that time the workforce was still dominated by Blacks and destitute Whites, but the population of Latinos (mostly Cubans, and Mexicans) was growing. Other workers started coming from Puerto Rico, and Tejanos (Mexicans from Texas) came from southeast Texas to work in Immokalee during the 60’s.

In 1980, Fidel Castro’s regime announced that Cubans were free to emigrate to the US from a single port, Mariel. The US welcomed the Cubans from this “Freedom Flotilla”, as refugees. Although not as welcomed by the Americans as the Cubans, Haitians came along with them by the thousands, many staying in Miami, and others moving on to rural communities, like Immokalee.

Guatemalans first came to the Immokalee area in the early 1980’s. In the mid-1980s they were able to file asylum claims because of the war in their home country.

In the 80’s new immigrants arrived in Immokalee every day with no money and no place to stay. They needed to live in proximity to the parking lots where buses picked up workers for the fields, so the south side of Immokalee became more and more crowded. The place named “Immokalee” from the Seminole word for “My Home”, had no room for the hopeful workers. They slept under trailers, under trees, in cardboard boxes. Once they worked and were able to save a little money, they could rent a place to stay. Slumlords, however, charged exorbitant prices for them to share a trailer or room or shack with other immigrants.

In the 1990’s the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), and the devaluation of the Mexican peso, made it easier for farmers in Mexico to compete with American growers, and subsequently, the influx of immigrants settled down to a more steady pace. Florida’s tomato revenues went down 20% during that time; some tomato companies in Immokalee went out of business. Still, Immokalee remained one of the first places new immigrants came.

The immigrants arrived in Immokalee with only a few dollars and their clothes in a bag, and they spoke no English. They came to Immokalee because they heard there was work there. Once here, they work in the fields of all winter, sending what they can back to their loved ones in their home country. At the end of the season, they pack everything they own into bags and migrate north for the summer season to follow the crops. (3)

Figure 1: Migrant farm workers picking tomatoes in Florida. Photo from Britannica Online for Kids (4)

The Men and Women Who Pick the Food We Eat

Facing extreme poverty in their home countries, men and women come at great risk to Immokalee with a deep hope for a better life. Today Mexicans make up over 50% of Immokalee’s population. 8-10% are Haitians, and 5-10% Guatemalans. (3) Many leave behind family members, including children or ailing parents unable to make the risky journey. Many speak only their native dialects, having no English skills and in fact, very little Spanish. They come with little education, but they nurture great courage in the face of the unfamiliar culture, harboring the hope that they may be able to earn money to send home to their families. They come prepared to work hard, and are driven by desperate need.

Since the Bracero Program, legal immigration has become very difficult for Mexicans. Immigration from any country requires a sponsor (a company or close relative who is a permanent resident or US citizen) to petition to bring them in. Even with a sponsor, the limit on visas issued per year per country means that a potential immigrant might have to wait years before a visa becomes available. Because of this, many prospective migrants turn to “coyotes,” smugglers who facilitate the migration to America, for a price. Many of these migrants show up at the fields of Immokalee, where they work for cash. (3) According to the National Agricultural Workers Survey (NAWS), half of all hired crop farmworkers lack legal authorization to work in the United States. (5)

Picking tomatoes is “piecework”, which means workers are paid by the bushel picked, not by the hour. Fresh market tomatoes must be picked by hand, because splits, dents, and gouges from automated machines are unacceptable in a fresh tomato. In this way, the fresh-market tomato agricultural methods in Immokalee differ from those whose tomatoes are destined for canning purposes; canning tomatoes are harvested by machine.

Because they are paid by the bushel, workers must be fast and able to endure long (usually 12-hour) days of back-breaking work. They must also be able to run their bushel baskets quickly to the waiting truck; those workers assigned areas farther from the truck are paid less, because they are forced to spend more time running than picking. On average, workers pick 20 buckets per hour. (6) Without even considering running time, that means the workers fill a bucket in about three minutes time.

I wanted to have first-hand experience of farming myself, so this past summer I volunteered to work part-time on an organic produce farm in central Illinois. Since the tomatoes were destined for local markets, we harvested only the fruits that had ripened on the vine, so extra care was needed in handling the tomatoes because of their ripened tenderness. Instead of bushel baskets, in which the weight of tomatoes would certainly crush those on the bottom, we used very shallow baskets. In contrast to the three-minute average picking time achieved by the workers described above, I was only able to pick one shallow bucket in about a half-hour’s time. The experienced farm hands were able to pick much faster than I, but were still significantly slower than three minutes per bucket. This experience gave me a real appreciation for the kind of work demanded of migrant workers. In order to fill a bushel basket with tomatoes, albeit solid fruit, those workers’ hand and arm movements must be lightning fast.

The pay for workers is no different than it was 30 years ago, and when adjusted for inflation, it’s about half of what it was then (7). Because they don’t have their own vehicles, workers are bussed to the farms. They are not compensated for time spent waiting for morning dew to dry, or for inclement weather. Less than a tenth of migrant farmworkers have health insurance, and they seldom receive overtime pay. The 2008 Profile of Hired Farmworkers (5) reports that, at $350, the median weekly earnings of full-time farm workers are only 59% those of all wage/salary employees, and that migrant farmworkers earn even less than settled farmworkers. Because of the seasonal nature of their work, harvest weeks are limited, and farm workers in Florida report annual incomes of between $7000 and $9000. (6)

Their health is poorer, and their children face more difficult educational challenges than their settled peers. The housing conditions are substandard because of “crowding, poor sanitation, poor housing quality, proximity to pesticides, and lax inspection and enforcement of housing regulations.” Agricultural work is “among the most hazardous occupations in the United States, and farmworker health remains a considerable occupational concern. Farmworkers face exposure to pesticides, risk of heat exhaustion and heat stroke, inadequate sanitary facilities, and obstacles in obtaining health care due to high costs and language barriers.” (5)

When we as American consumers purchase cheap tomatoes that come from the farms of Immokalee, we are benefitting from a system that is unfair to the workers. The men and women who work the fields are essentially subsidizing the price of our cheap tomatoes through their lack of fair wages for the dangerous service they provide.

Chemical Exposure

Because of the poor soil quality in Florida, research to improve growing conditions for tomato production began in the mid 1940’s. Growers avoided increases in various plant pathogens and weeds associated with repeated cropping, by moving their growing enterprises to previously un-cropped land every couple of years. However during the late 1950’s, the availability of inexpensive land was reduced due to the growth of urban populations competing for the land, and growers faced the dilemma of having to reuse the same land for their crops in order to be profitable. In order to control a complex known as “old land disease” in fresh market tomato crops, a system was developed in the 1960’s that included in-the-row fumigation, followed by the application of a polyethylene mulch and fertilizers, with maintenance of a high water table. This system was widely employed to enable the frequent re-use of the land for tomato crops. Modified and improved since the 1970’s, it is still the system of choice for the majority of Florida tomato growers. (8)

Over 30 chemicals are routinely sprayed onto a tomato field during the growing season (9). Many are rated highly toxic and some (metribuzin, mancozeb, and avermectin) are known to be “developmental and reproductive toxins”, according to the Pesticide Action Network (10).

Pesticide exposure results in toxic effects that can be both acute and chronic. Depending on the classification of the pesticide, symptoms may vary, but acute symptoms include blurry vision, headache, dizziness, fatigue, diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, heavy sweating, muscle or abdominal pain, tremors, lack of coordination, confusion, skin irritation, irritability, sensitivity to sound or touch, blindness, fingernail loss, nosebleeds, loss of appetite, twitching muscles, difficulty walking, talking, and concentrating, convulsions, unconsciousness, difficulty breathing, coma, and even death. (11)

Chronic health impacts include many types of cancers and neurological effects. Many years after the exposure, large numbers of people who have suffered serious acute poisoning have “significantly impaired hearing, vision, intelligence, coordination, reaction time, memory, and reasoning.” Cognitive symptoms of chronic damage to the nervous system “include personality changes, anxiety, irritability, and depression.” Fertility can be affected through damage to men’s and women’s reproductive organs, as unfortunately many have learned to their deep sorrow. Many pesticides that persist for long periods in the environment are also known to be endocrine disruptors. (11)

When pesticides are used, the US Environmental Protection Agency requires a certain amount of time to pass before workers may return to the fields. Workers have reported violations of this regulation, stating that they were ordered to pick the fruit during the safety interval.

In the United States, government estimates indicate more than 20,000 farmworkers out of 5 million or more workers in this country suffer acute pesticide poisonings per year. As for chronic impacts, no serious effort has been made to develop estimates of annual cases, because of the difficulty in linking the effects to the pesticides. At the global level, the World Health Organization estimates that three million acute pesticide poisonings occur each year, including 220,000 fatalities. (11)

One of those workers affected by pesticides was 19-year-old Francisca Herrera. She worked in fields that had recently been sprayed with mancozeb, 24 to 36 days into a pregnancy (12). Her son Carlos was born without arms or legs, a rare condition called tetra-amelia syndrome. “When you work on the plants, you smell the chemicals,” she said. “It has happened to me many times that when you are working and the chemical has dried and turned to dust that you breathe it.” (7)

Regulations require that workers use protective eyewear, gloves, rubber aprons, and vapor respirators. Herrera said she had not been warned of the dangers or advised of the protective regulations. She felt sick with nausea, dizziness, and burning eyes the entire time she worked in the field. She subsequently developed rashes and open sores.

Herrera’s boss, a subcontractor to Ag-Mart, told her that if she did not work, she would be kicked out of the room he was providing. Because of her pregnancy, she needed a place to live, so despite her illness she continued to work. Even after quitting the fields for the childbirth, she continued to hand-wash the chemical-soaked clothes of both her husband and brother.

After Carlos’ birth, he needed constant medical attention. Although by birth he was an American citizen, Herrera and her husband were undocumented and at risk of deportation. There was not much they could do for their son.

Florida surpasses most other states in its use of pesticides and toxic chemicals. For example, in 2006, Florida’s tomato farmers applied nearly eight million pounds of insecticides, fungicides, and herbicides, compared to only one million in California (7). This is likely because the conditions in Florida are not conducive to growing tomatoes, because of the lack of rich soil and also because of the high number of pests that thrive year-round in the Florida sunshine.

In 2006, the Florida Department of Health reported only two definite or probable cases of harmful pesticide exposure among its agricultural workforce of roughly 400,000 men and women. California, with only three times the number of workers, reported 200 cases. Because of the higher risk of exposure in Florida, this may be evidence of a lack of enforcement of regulations.

In both Florida and California, physicians are required to report cases of pesticide poisoning. But in Florida that law is “unenforced and ignored” (7). The director of the hospital where Herrera’s deformed baby Carlos was born said he wasn’t even aware of the regulation.

According to a 1997 report, “Indifference to Safety: Florida’s Investigation Into Pesticide Poisoning of Farmworkers,” Florida enforcement of safety regulations meant to prevent avoidable exposure and injury came up short:

· The State repeatedly failed to find a causal connection between pesticide exposure and the injuries suffered by farmworkers.

· The State found regulatory violations in 31 instances, but issued only two fines.

· The State failed to adequately investigate poisoning complaints even when a farmworker was seriously injured or killed, by systematically: failing to interview co-workers or other eyewitnesses out of the presence of supervisory personnel (with adequate translators); failing to obtain relevant medical records; routinely accepting uncorroborated employer claims of compliance; using checklists as a substitute for a thorough on-site inspection; and ignoring evidence of employer retaliation.

· The State lacked adequate investigative protocols.

· The State failed to coordinate the investigative efforts of FDACS and other enforcement agencies, such as OSHA.

· The State failed to impose meaningful penalties when pesticide violations resulted in worker injury. (13)

This indifference to worker safety on the part of the state has resulted in a corresponding indifference on the part of the landowners, who take advantage of the lack of enforcement to improve efficiency of their farming processes, at the expense of the workers.

Most cases of illness from pesticide exposure go unreported. Workers are not trained to recognize symptoms of pesticide poisoning, which can be similar to the common cold or flu. They do not have health insurance and many workers are undocumented, so they avoid visits to the doctor in any case. Many are embarrassed to be seen as weak, so continue to work through their illnesses. In many cases, they are threatened with termination if they miss work due to illness, or report being sprayed.

One example was Guadalupe Gonzales III, who arrived at work in 2005 at 7 AM, at a farm operated by Thomas Produce Company, then one of the biggest players in the Florida produce business. Gonzales did not report directly to the farm, but to a contractor, or “crew boss,” Raul Humberto Ruiz. Gonzales’ assignment that day was to apply methyl bromide.

The EPA classifies methyl bromide as a “Category I Acute Toxin,” the most deadly category. The label instructions on the chemical container read “All persons working with this fumigant must be knowledgeable about the hazards, and trained in the use of the required respirator equipment and detector devices, emergency procedures and proper use of the equipment.” Gonzales claimed that he had not received training, and was not even told the name of the pesticide, and he was wearing a short-sleeved shirt. By 11:00, his head started aching, his eyes stung, and he experienced severe chest pains. Instead of sending him to a medical facility for treatment, the crew leader told him to sit in the air-conditioned truck. After a while Gonzales felt better, so returned to work, but that evening his condition worsened, and he went to the emergency room. Two days later he returned to the fields and his symptoms returned, so he filed for worker’s compensation. He reported that his boss fired him saying, “If you keep feeling bad, I can’t keep you as part of the crew anymore.” Gonzales lost his job for following protocol. Ultimately, the state fined the company $5000, a slap in the wrist. The fine was later reduced to $3500 on appeal. (7)

Another example of this indifference to safety was Victor Grimaldi. He recalled his first day on the job: “I was taken into the office, and the first thing the boss said was, ‘Sign this!’ It was a document written in English, which I don’t read or speak, but I needed work, so what was I going to say?” Grimaldi was then shown a pesticide-handling safety video, also in English, but he was able to understand a little bit from the context of the graphics. He was given a backpack-mounted tank full of pesticide, and told to start spraying a row of tomatoes. Eventually he came to a group of pickers, so he moved around them. When the boss asked him why he moved, Grimaldi replied that he had just seen a video showing that spraying near people was against the law. “I’m the law out here,” the boss replied, and ordered Grimaldi to return to the row with the pickers.