The following is a presentation I gave to my Community Health class. I was the final presenter in my group of six, on the topic of healthy food access. The others talked about:

- What is a food desert

- Healthy food access in Chicago

- How does Chicago compare to other urban areas

- Intervention efforts

- What is healthy food

My part was on “The global challenge”. Although my group did a spectacular job with their respective parts, I am only including my own contribution in this blog.

The Global Challenge

When the topic of feeding the world comes up, the first thing we think of is the problem of the world’s population, now at 7 billion, increasing beyond the earth’s capacity to feed us all. We forget that the context of the food security challenge includes many other factors:

- Urbanization

- Growing Inequities

- Human Migration

- Globalization

- Changing Dietary Preferences

- Climate Change

- Environmental Degradation

- Trend Towards Biofuels

In 2002, the World Bank and United Nations collaborated to carry out a consultation to determine whether an in-depth assessment of international food security was needed. Two years later, they concluded that such an assessment should be undertaken, and they launched a massive, international effort that resulted in a 600-page scientific report, prepared by 400 experts from 52 countries. There were two rounds of peer reviews by 400 reviewers from 45 countries, including governments, organizations, and individuals.

58 countries accepted the final report in 2008, plus an additional three (yellow), which accepted it with reservation:

The objective of this report is clearly stated:

This Assessment is a constructive initiative and important contribution that all governments need to take forward to ensure that agricultural knowledge, science and technology (AKST) fulfills its potential to meet the development and sustainability goals of:

- The reduction of hunger and poverty

- The improvement of rural livelihoods and human health, and

- Facilitating equitable, socially, environmentally and economically sustainable development

A section of the report included a summary of ten concerns, of which I only presented three. All ten were given out as a handout, for reference:

Agriculture At A Crossroads: Global ReportConcern #1The fundamental failure of the economic development policies of recent generations has been reliance on the draw-down of natural capital Concern #2Failure to address the “yield gap” Concern #3Modern public-funded AKST research and development has largely ignored traditional production systems for “wild” resources Concern #4Failure to fully address the needs of poor people (loss of social sustainability)

Concern #5Malnutrition and poor human health are still widespread

Concern #6Intensive farming is frequently promoted and managed unsustainably, resulting in the destruction of environmental assets and posing risks to human health

Concern #7Agricultural governance and AKST institutions have focused on producing individual agricultural commodities (e.g. cereals, forestry, fisheries, livestock), rather than seeking synergies and integrated natural resources management. Concern #8Agriculture has been isolated from non-agricultural production-oriented activities in the rural landscape:

Concern #9Poor linkages among key stakeholders and actors Concern #10Since the mid-20th century, there have been two relatively independent pathways to agricultural development:

o Agricultural R&D o International Trade

o Relevant to local communities (IAASTD, 2009) |

Concern #1

The fundamental failure of the economic development policies of recent generations has been reliance on the draw-down of natural capital.

- 80% of oceanic fisheries are being fished at or beyond their sustainable yield

- The world’s forests lose a net 5.6 million hectares (an area the size of Costa Rica) each year

- Half the world’s population lives in countries that are extracting groundwater from aquifers faster than it is replenished

(Brown L. R, 2012)

Concern #5

Malnutrition and poor human health are still widespread

- Research on the few globally-important foods (cereals) has been at the expense of meeting the needs for micronutrients

- Wealthier consumers are also facing problems of poor diet

- Increasing concerns about food safety

The USDA recommends that fruits and vegetables comprise about 50% of our food plate, yet fruits and vegetables represent only about 35% of global production. Grain production, on the other hand, represents about twice the amount recommended for a healthy diet.

In my pie chart, I split out corn from the rest of grain production, because corn is an interesting product in our food supply. Not only does this single crop dominate the rest of food production, but it is used for many things besides food. For example, about 30% of the corn crop is used for high fructose corn syrup. Another 30% is used for fuel. This is a problem, because the price of food in our market system is inextricably linked to the price of fuel.

What is driving the disparity between the USDA plate and global production? Is it supply, or demand? If demand, who is fueling that demand – could it be the suppliers? Something to think about.

Concern #6

Intensive farming is frequently promoted and managed unsustainably, resulting in the destruction of environmental assets and posing risks to human health

- Land clearance

- Soil erosion

- Pollution of waterways

- Inefficient use of water

- Dependence on fossil fuels (agrochemicals/machinery)

The Water Cycle: The existence and movement of water on, in, and above the Earth, between the atmosphere, land, water bodies, and soil. Earth's water is always in movement and changing states, from liquid to vapor to ice. The water cycle—a physical process—including the movement and changing state of water affects plant and animal (including human) life.

The Mineral Cycle: The movement of minerals or nutrients including carbon, nitrogen and other essential nutrients. This physical cycle affects plant, animal and human life.

Energy flow: The most basic physical processes within an ecosystem are photosynthesis and decomposition. Energy flow describes the movement of energy from the sun through all living or once living things.

Community Dynamics (Succession): Ecosystems, plant and animal communities are ever changing. Community dynamics, a biotic process, describes the never-ending development of biological communities.

Source: Essig, 2013

Nature is full of cycles; it is when those cycles are broken that a process becomes unsustainable. To be sustainable over the long term, farming processes and methods should respect the cycles of nature. These four critical cycles are four panes in the window of our ecosystem; all work together synergistically in a healthy system.

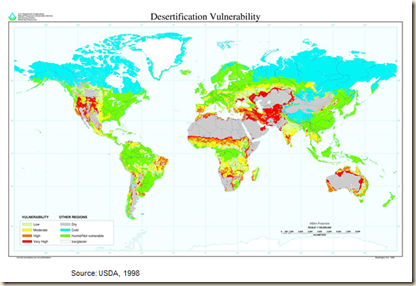

Desertification Vulnerability

- Dust storms carrying 2-3 billion tons of soil leave Africa each year

- Roughly ⅓ of the world’s cropland is now losing topsoil faster than it can be reformed

(Source: Brown L.R., 2012)

Holistic Management

After and Before: Kariegasfontein ranch in Aberdeen, South Africa (Savory Institute, 2014)

Alan Savory is leading an effort using a paradigm he calls “Holistic Management,” resulting in successful healing of deserts: 15 million hectares on five continents. He claims that slight increases in organic matter over huge portions of the earth’s land surface area, would result in putting masses of carbon “back where it belongs – in the soil – and more importantly, where it can actually do some good. Organically rich soils feed soil bacteria, protozoans, and fungi, active populations of which lead to ever greater plant-available nutrients and less dependence on outside fertilizer inputs.” (Savory, 2013)

Healing Tree Farm

Healing Tree Farm, near Traverse City, MI, 26 May 2013

Intensive use of pesticides kills the soil.

The green portion of land in this photo is near the farmhouse; pesticides were not applied there. The brown portion was a field that received heavy pesticide and fertilizer inputs for several years. Not much will grow there now, not even weeds, without significant quantities of inputs. The land is now being transitioned to a permaculture demonstration farm. The land will eventually heal over several years, given healthy management.

I have a favorite quote about the importance of soil from a farmer friend whom I respect and admire very much, Henry Brockman:

Highly nutritious food comes from a healthy soil that is part of a healthy farm that is part of a healthy environment. This circle of health is generated by farming practices that are based on the goal of protecting and enhancing all life, from the lives of the insects, worms, and arthropods of the vegetable field to the lives of the wildlife and domesticated life who inhabit the environment around the field.

The basic tenet of this kind of farming is to protect and enhance the tiny lives of the microorganisms of the soil.

Synthetic fertilizer, which should be a life-promoting substance, actually deals in death. And it deals in death in many ways, polluting air and water as well as killing soil life and disrupting the soil’s intricate system for naturally providing plants with nitrogen. (Brockman, 2001)

Phosphorus

Source: Elser & Rittmann, 2013

The ‘P’ in ‘N-P-K’ fertilizer is for phosphorus, one of the most important nutrients to plant and animal life. Traditionally, ground-up rock phosphate has been applied sparingly to farmland; it is not water soluble so the phosphate becomes available to plants only very slowly, over a period of years. In recent years the industry started treating the phosphate rock with acid to make it water soluble: “super phosphate”. This is used in industrial farms and is immediately available to plants, resulting in significant growth. That’s all well and good, except that excess phosphate, being water soluble, leaches into the ground water and makes its way to streams and rivers, and eventually to the oceans. There is a dead-zone in the Gulf of Mexico where no aquatic life can exist, because of this problem. (Herman Brockman, in Gelder, 2012)

- 20 million metric tons of Phosphate in fertilizers were applied in 2012 worldwide.

- Phosphorus comes primarily from Morocco (75%), #2: China (5.5%), #7: US (2%)

- Phosphorus use tripled between 1960 and 1990 (IAASTD, 2009)

- Extrapolating this trend, the US will become entirely reliant on imports within 3-4 decades. (Elser & Rittmann, 2013)

The series of phosphate cycles shown above illustrate a potential solution to upcoming phosphate shortages. The “current” cycle shows that mined phosphorus is the source of about 90% of the phosphate used to fertilize soil and crops; another 10% comes from weathered phosphorus. The phosphorus mines are limited. Another source of phosphorus that is currently only minimally tapped, is from animal, food, and human waste.

If we were to do a better job of recycling the phosphorus from our waste, we would reduce the need for the water-soluble fertilizer, reduce erosion and runoff into the water, the water would become less polluted, enhancing the survival of fish populations, as shown in the “transition” and “implemented” cycles of the series above.

Water

Source: Brown L. R., 2012

Are Industrial Methods Necessary?

Source: Liebman, 2008

The agriculture industry tells us that, despite the pollution to our water, air, and soil, despite the depletion of resources such as phosphorus, water, and fossil fuels, despite the health risks of pesticides and the super weeds and the antibiotics and the CAFOs, if we did not farm the way we do, we would not be able to feed our 7-billion mouths. Is this claim true?

A long-term (10 year) study was recently undertaken by Iowa State University, funded by a grant from the USDA. They compared the conventional 2-year corn/soybean rotation typically used, with longer, 3- and 4-year rotations that included one year of red clover, and two years of alfalfa, respectively. With each rotation paradigm, they also compared transgenic crops grown using high inputs of pesticides, with non-transgenic crops grown with minimal use of pesticides.

The results are in. They found the following:

- The 3- and 4-year rotation systems exceeded the 2-year conventional systems in yield by 4-20%.

- Weed biomass was low in all systems without significant variation.

- Net returns were highest for 3-year non-transgenic system, and lowest for the two-year non-transgenic system.

Their conclusion:

These results indicate that substantial improvements in the environmental sustainability of Iowa agriculture are achievable now, without sacrificing food production levels or farmer livelihoods. (Liebman, 2012)

The Global Report also had this to say:

Small farms are often among the most productive in terms of output per unit of land and energy.

And:

Restoration techniques are available, but their use is inadequately supported by policy. (IAASTD, 2009)

It is possible to feed our population, but we have our work cut out for us to help establish the policies that can facilitate equitable, socially, environmentally, and economically sustainable development.

Regulatory change will not happen overnight. Until it does, we can each do our part to influence the transition to sustainable farming methods, by voting with our fork.

I have made a personal commitment to consume food that has been organically grown, using sustainable methods that enhance the health of our soil and ecosystem. I know that this is not possible for many, and it did not happen over night for me; I have been working on this for several years now, taking small steps at a time.

When we talk about food deserts, we are referring to areas where healthy food is not available. We usually think of healthy food in terms of fresh fruits and vegetables. But, if we were to extend our definition of healthy food to food that has been grown to support the health of the environment, we would discover that most of us actually live in a food desert.

Because of my personal commitment, I have searched for organically grown food near campus. I have inquired at every restaurant on Taylor Street between the East and West campuses. The closest restaurant I have been able to find is across the street from the Sears Tower, two miles away. Organic food is also available at the Whole Foods on Canal and Roosevelt Rd. These locations are hardly close enough for me to walk to between classes to buy a lunch, so I pack my own lunch and carry it around with me to all my classes in my backpack. We are in a food desert here on campus.

At home, the nearest Whole Foods is over three miles from my home. The nearest farmer’s market that provides organically grown local produce is about 30 miles away from my home. I live in a food desert. Therefore, I am working on transitioning my backyard to a garden so that I can grow my own produce.

If more people would insist on consuming produce that has been raised sustainably, more farmers would make the effort to respond to the demand. We do not have to wait for our government to do the right thing; each of us can do what we can in our own way, to support the movement towards healing our earth.

References

Aneki.com. (n.d.). Map of the World. Retrieved March 31, 2014, from Aneki.com Rankings + Records: http://www.aneki.com/map.php

Brancaccio, D. (2012, April 30). Soybean prices on the rise, could impact other food sources. Retrieved from Marketplace Morning Report: http://www.marketplace.org/topics/economy/soybean-prices-rise-could-impact-other-food-sources

Brockman, H. (2001). Organic Matters. Congerville: TerraBooks.

Brown, L. (2012). Full Planet, Empty Plates: The New Geopolitics of Food Scarcity. New York: W.W. Norton & Company.

Brown, L. R. (2012). Presentations for Full Planet, Empty Plates: The New Geopolitics of Food Scarcity. Retrieved March 29, 2014, from Earth Policy Institute: http://www.earth-policy.org/books/fpep/fpep_presentation

CME Group. (2014, March 1). Agricultural Commodities Products. Retrieved March 29, 2014, from CME Group: http://www.cmegroup.com/trading/agricultural/

Earth Policy Institute. (2014, February 25). Food and Agriculture. Retrieved March 31, 2014, from Earth Policy Institute: http://www.earth-policy.org/data_center/C24

Elser, J. J., & Rittmann, B. E. (2013, December 25). The Dirty Way to Feed 9 Billion People. Future Tense. Retrieved March 31, 2014, from http://www.slate.com/articles/technology/future_tense/2013/12/phosphorus_shortage_how_to_safeguard_the_agricultural_system_s_future.2.html

Essig, M. (2013). Nurturing Our Planet: The Health Of The Ecosystem Processes. Savory Institute.

Gelder, M. (2012, November 16). Interview with Herman Brockman about GMOs. Retrieved March 30, 2014, from Mary's Heights Blogspot: http://marysheights.blogspot.com/2012/11/interview-with-herman-brockman-about.html

IAASTD. (2009). Agriculture at a Crossroads: Global Report. International Assessment of Agricultural Knowledge, Science and Technology for Development. Retrieved March 29, 2014, from http://www.unep.org/dewa/assessments/ecosystems/iaastd/tabid/105853/default.aspx

Liebman, M. (2008). Mixed Annual-Perennial Systems: Diversity on Iowa's Land. Iowa: Leopold Center, Iowa State University. Retrieved March 31, 2014, from http://www.leopold.iastate.edu/sites/default/files/events/Matt_Liebman_presentation.pdf

Liebman, M. (2012). Impacts of Conventional and Diversified Rotation Systems on Crop Yields, Profitability, Soil Functions, and Environmental Quality. Leopold Center for Sustainable Agriculture. Iowa State University. Retrieved March 31, 2014, from https://www.leopold.iastate.edu/sites/default/files/grants/E2010-02_0.pdf

Savory Institute. (2014). Desertification Solution: Holistic Management. Retrieved March 30, 2014, from Savory Institute: http://www.savoryinstitute.com/science/the-desertification-crisis/desertification-solution-holistic-management/

Savory, A. (2013). The Foundation of Holistic Management: New Principles & Steps For Handling Complex Decisions, E-Book One. Savory Institute. Retrieved from http://savory-institute.myshopify.com/products/holistic-management-principles-new-principles-steps-for-handling-complex-decisions

USDA. (1998). Natural Resources Conservation Service Soils. Retrieved March 29, 2014, from United States Department of Agriculture: http://www.nrcs.usda.gov/wps/portal/nrcs/detail/soils/use/worldsoils/?cid=nrcs142p2_054003

USDA. (1999). Feed Yearbook. (D. Decker, Ed.) U.S. Department of Agriculture, Market and Trade Economics Division, Economic Research Service.